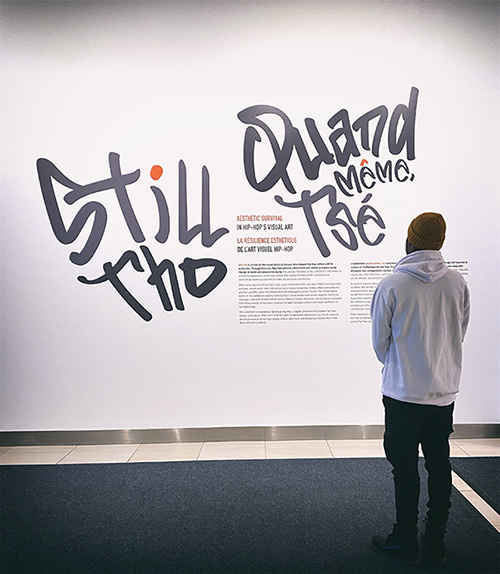

Still Tho: Aesthetic Survival in Hip-Hop’s Visual Art

Curatorial statement, Mark V. Campbell

Still Tho is an ode to the visual artists in Canada who shaped hip-hop culture and its aesthetics. Through their art, they have placed justice front and centre to inspire social change at home and around the world. The phrase “Still tho” in the exhibition’s title refers to a common expression in hip-hop culture that speaks to these artists’ perseverance, overcoming numerous barriers to make art and build community.

While some aspects of hip-hop’s early years in the late-1970s and early-1980s have been well archived, visual works from that period were mostly temporary. Artists often overwrote one another’s graffiti, while the natural elements destroyed outdoor murals. The mixed-media works in this exhibition explore how hip-hop’s visual artists have woven together historical, nostalgic, and archival elements to leave a physical legacy. Moreover, the exhibition highlights the lasting impact of hip-hop’s visual art on both Canadian culture and visual aesthetics in our digital age.

This exhibition is inspired by Northside Hip Hop, a digital collection of Canadian hip-hop history and culture. After more than ten years in operation, Northside is turning its focus to the visual aspects of hip-hop culture whose ephemeral and temporary nature often make them difficult to archive.

Knowledge of Self

Beyond the four foundational elements of hip-hop culture (bboying, djing, emceeing, and aerosol art), many consider knowledge of self to be a fifth foundational element. Knowledge of self can be defined as a heightened awareness of self in relation to the oppressive and discriminatory power of social institutions and processes, something that resonates throughout the various works in the exhibition. Many of these works explore and take inspiration from the height of knowledge of self in hip-hop from the late-1980s to the mid-1990s—when artists and emcees openly reflected a heightened level of social consciousness.

In Coltan Kills (2015), Eklipz flips contemporary messages that promote overconsumption to illuminate the mobile phone industry’s reliance on minerals that are extracted from conflict zones—and often by child soldiers.

With a similar level of criticality, Kalkidan Assefa’s Don’t Shoot (2016) heightens awareness of the continued murders and excessive uses of force that incite the Black Lives Matter movement. Here the central figure’s angel-like wings cannot carry away the unarmed youth swiftly enough, while his Afro reverberates with an Afrofuturist flavour that promises transcendence beyond the present moment.

In a similar vein, Mark Stoddart’s Fight the Power (2016) reflects generations of police brutality and excessive force visited upon the bodies of people of African descent, capturing the continuities between the murder of the fictional character Radio Raheem in Spike Lee’s film Do the Right Thing (1989) and the eerily similar murder of Eric Garner, in real life, more than thirty years later.

Altogether, these works exemplify how hip-hop’s socially conscious past continues to animate today’s generation of artists for whom justice unequivocally remains central.

An archival sensibility

Several works from the exhibition question the ephemerality of graffiti as they resist both the physical act of erasure and the loss of memory that often happens when a mural fades away.

In Fantasia 1987 – Hail the Lizard King (2020), Curly pays tribute to an iconic Edmonton graffiti mural from 1987 that has motivated generations of artists in that city to begin graffiti writing. Curly’s recreation of this piece on canvas for the Still Tho exhibition stands in juxtaposition to the delicate reality that sees many hip-hop pieces last less than a week before others overwrite it.

In Evolution of Graffiti and Revolt (2011), EGR uses her imagination to tackle and expose the problematics of beautification with Toronto’s 2011 campaign to eliminate graffiti. Moving away from her more public concerns about the future of graffiti, EGR Art on Vintage Spray Cans (2007) takes images of her older works and adds them to vintage spray cans—capturing a sense of the archival while also emphasizing how women occupied important spaces in hip-hop culture prior to the 1990s when major record labels infiltrated and bolstered a hyper-masculine reputation for the culture.

Elicser Elliott’s Untitled (2010) also harkens back to the pre-1990s era with a painting of Soundwave, the blue boombox character from the 1986 cartoon The Transformers who was subsequently missing from the 2007 blockbuster adaptation.

Like hip-hop music’s use of sampling and remixes, these works speak to the culture’s powerful ability to resist erasure and retain memory.

Outside, beyond these streets

Both built and natural environments figure prominently in the work of artists throughout this exhibition.

In STARE’s S to the T (2019), concrete from the concrete jungle of the urban landscape serves as a canvas for the work.

In a similar vein, Mark Valino’s Moments of Movement: Freestyle Dances (2017-20) draws attention to creative repurposing of the environment as bgirls and dancers use various built and natural environments as stages for their performances.

Moving further from the city streets, Mique Michelle’s Dilo (2021) focuses on waterways to disrupt the urbanity at the core of hip-hop culture. Michelle’s piece reflects her process of continually unlearning colonial knowledge and returning to Indigenous ways of knowing and being. In turn, the piece reminds audiences of the environment’s centrality to our existence and of the fact that we are all treaty people who must continue to live with respect for Turtle Island (North America).